4.8 Complex Recursive Problems

In the previous sections we looked at some problems that are relatively easy to solve and some graphically interesting problems that can help us gain a mental model of what is happening in a recursive algorithm. In this section we will look at some problems that are really difficult to solve using an iterative programming style but are very elegant and easy to solve using recursion. We will finish up by looking at a deceptive problem that at first looks like it has an elegant recursive solution but in fact does not.

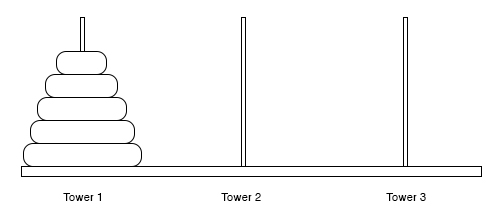

4.8.1 Tower of Hanoi

The Tower of Hanoi puzzle was invented by the French mathematician Edouard Lucas in 1883. He was inspired by a legend that tells of a Hindu temple where the puzzle was presented to young priests. At the beginning of time, the priests were given three poles and a stack of 64 gold disks, each disk a little smaller than the one beneath it. Their assignment was to transfer all 64 disks from one of the three poles to another, with two important constraints. They could only move one disk at a time, and they could never place a larger disk on top of a smaller one. The priests worked very efficiently, day and night, moving one disk every second. When they finished their work, the legend said, the temple would crumble into dust and the world would vanish.

Although the legend is interesting, you need not worry about the world ending any time soon. The number of moves required to correctly move a tower of 64 disks is $$2^{64}-1 = 18,446,744,073,709,551,615$$. At a rate of one move per second, that is $$584,942,417,355$$ years! Clearly there is more to this puzzle than meets the eye.

Notice that, as the rules specify, the disks on each peg are stacked so that smaller disks are always on top of the larger disks. If you have not tried to solve this puzzle before, you should try it now. You do not need fancy disks and poles–a pile of books or pieces of paper will work. Here are the three rules to be followed:

- You can only move one disk at a time.

- Only the "top" disk can be removed.

- No large disk can sit over a small disk.

How do we go about solving this problem recursively? How would you go about solving this problem at all? What is our base case? Let’s think about this problem from the bottom up. Suppose you have a tower of five disks, originally on the first peg. Our base case will be to move a single disk to peg three.

Here is a high-level outline of how to move a tower from the starting pole, to the goal pole, using an intermediate pole:

- Move a tower of height-1 to an intermediate pole, using the final pole.

- Move the remaining disk to the final pole.

- Move the tower of height-1 from the intermediate pole to the final pole using the original pole.

As long as we always obey the rule that the larger disks remain on the bottom of the stack, we can use the three steps above recursively, treating any larger disks as though they were not even there. The only thing missing from the outline above is the identification of a base case. The simplest Tower of Hanoi problem is a tower of one disk. In this case, we need move only a single disk to its final destination. A tower of one disk will be our base case. In addition, the steps outlined above move us toward the base case by reducing the height of the tower in steps 1 and 3.

function moveTower(height, fromPole, toPole, withPole) {

if (height >= 1) {

moveTower(height - 1, fromPole, withPole, toPole);

moveDisk(fromPole, toPole);

moveTower(height - 1, withPole, toPole, fromPole);

}

}

function moveDisk(fp,tp) {

console.log('moving disk from', fp, 'to', tp);

}

moveTower(3, 'A', 'B', 'C');

// moving disk from A to B

// moving disk from A to C

// moving disk from B to C

// moving disk from A to B

// moving disk from C to A

// moving disk from C to B

// moving disk from A to B